Episode 1 : Amphibians on the move

Every spring, frogs, salamanders and toads migrate throughout New England. During the trek, they often cross busy highways and roads – and many won’t survive the journey. This episode, we’re touching down in Keene, NH, to witness a migration and meet a group of volunteers who are helping their local amphibians to beat the odds.

This is the Animalia Podcast – an audio and photo blog series about wildlife and animals on our shared planet. I’m your host and producer, Anna Miller.

There’s been a mass migration happening in New England these past few weeks– and it could be happening right under your nose and maybe even in your own driveway while you are sleeping. Welcome to episode one.

Why did the frog cross the road?

It’s a rainy spring night in Keene, NH, as the sun begins to set. Rain drops fall on my windshield, and it’s a steady forty-three degrees outside.

It’s wet, it’s dark, and the snow has melted. Conditions are perfect.

This might seem like crummy weather, but this is exactly the kind of night the salamanders and frogs have been waiting for. They’re just waking up from hibernating all winter – and they’re making the annual journey to nearby wetlands and vernal pools to mate and lay eggs. This is the amphibian migration season in Keene, NH - and tonight they’ll be on the move.

But here lies the problem. These frogs and salamanders will likely have to cross a few roads to get there – and the odds are not in their favor. Hopping across pavement is a little bit like Russian roulette. Each year, countless numbers of amphibians are killed by cars.

And that’s where the Salamander Crossing Brigade comes in – a hardy group of locals who go out on rainy nights to move salamanders and frogs off the road.

“Oh I’m sure that many people think that we’re crazy for doing it!" says Brett Thelen, the science director for the Harris Center for Conservation Education. She leads citizen science programs in the region, including the volunteers (or salamander people) who are out here tonight. "For some people, they see the value in it but it's just not their cup of tea. But for the people who love it, they come aback year after year. It’s like a community of salamander people which is really cool. But I could totally understand why people woudn’t want to do this!"

Amphibians receive a helping hand

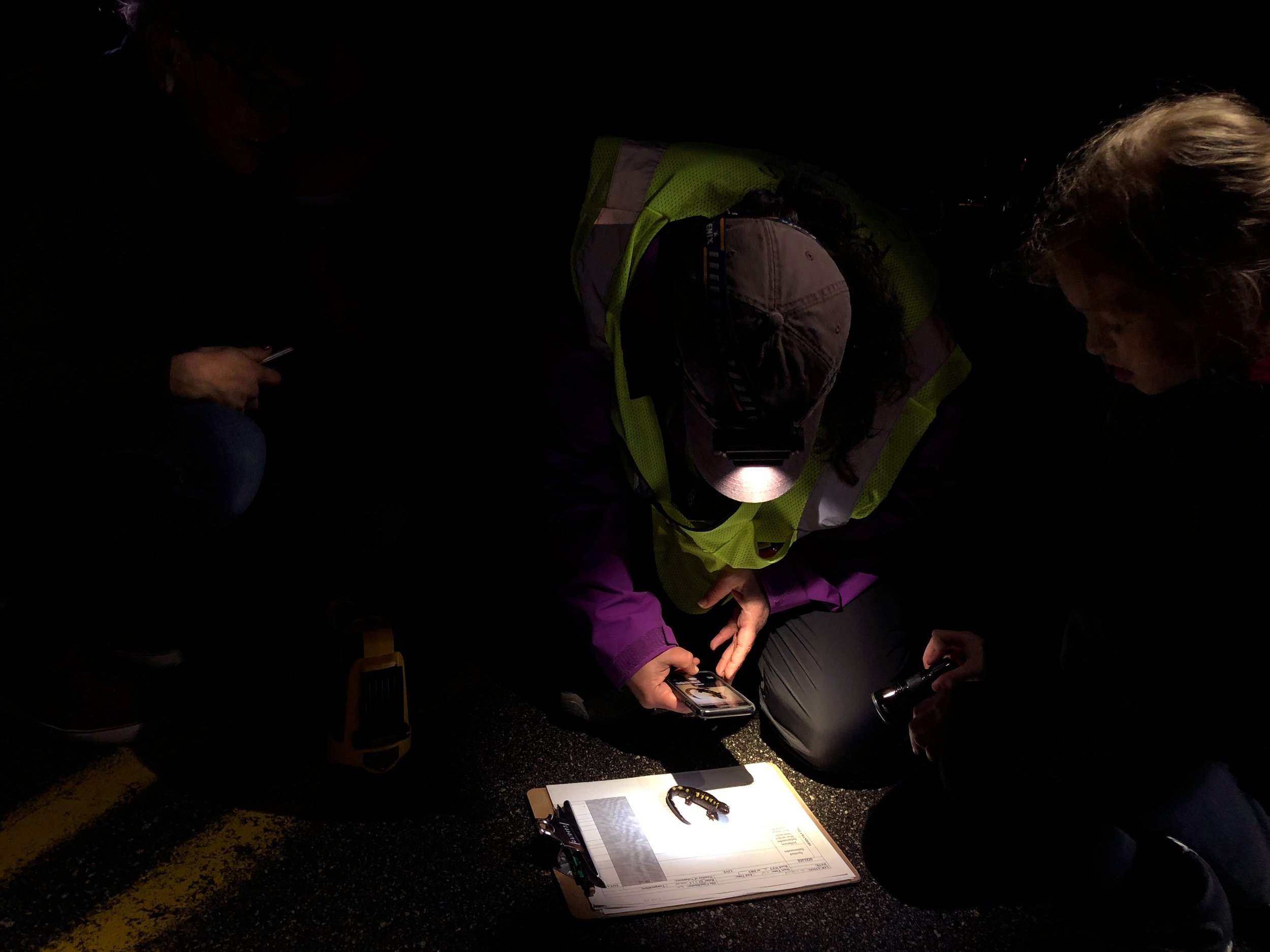

Brett is out here almost every rainy night. She wears a reflective vest and holds a flashlight, scanning the pavement for any creatures that might need a hand.

“Basically, we’re just going to walk back and forth down the road, shining our flashlight and looking for frogs in the road and salamanders," says Thelen. "We pick them up when we see them, and keep count of what we find by species and whether they are alive or dead. And in fact I see a wood frog, so I’m going to hustle up there to grab that before any cars come through."

Brett is constantly on the move, and it’s honestly hard to keep up with her. She jogs up and down the road in her swishy rain pants, gently picking up frogs in both hands, and carrying them to the other side - making sure that the animal is still going in the same direction as before.

And that’s actually important.

You see- these frogs just aren’t just hanging out – they are on a mission. They are crossing the road to reach a specific destination – their local vernal pool or wetland to lay eggs.

Vernal pools are temporary bodies of water - glorified puddles basically – that form in the springtime from melted snow and rain water –and they are the perfect nurseries for salamander and frog eggs.

it’s the ideal place to incubate a brood because they don’t have fish or major predators in them - so the eggs have the best chance of survival…. that is if the frogs and salamanders can survive the journey to get there in the first place.

Tonight, amphibians are migrating both in and out of the vernal pools and wetlands, crossing the road in both directions. Brett marks each amphibian species on her clipboard, and includes their direction of travel.

Brett has been out here for years, but she still gets excited. I ask her if she has a soft spot for one species in particular.

"Oh, I love them all. I really love… my favorites are probably grey tree frogs and toads. But I really admire wood frogs for their tenacity and their ability to come out on these really cold, cold, early spring nights when you can’t imagine that any amphibian could possibly be stirring. And yet, there they are...And toads are so cool because they always look grumpy and I love that about them. And everybody loves spotted salamanders because they are incredible. They are really charismatic….So I guess I have four or five favorites. But its good to have many favorites right? Instead of just the one."

Brett isn’t alone out here on this rainy night– there’s a handful of volunteers out here doing the same thing – picking up frogs with the same level of enthusiasm.

"Oh hi, We’re going to help this. Nice woodfrog, I believe. We’re going to take a closer look. (Gasps.) Look. Beautiful!" says Bill Strupe, a salamander crossing brigadier from Keene, NH.

I ask Bill what the frog feels like.

"Oh Really soft! This one is as squishy as an easter candy! But a little colder."

"One thing I like about the crossing brigades is that it turns upside down your sense of what’s good weather. Because most of the time, people think of good weather as its 72 and you just want to have a margarita and put up your feet. But now it can be 49 and rainy and I think here we go! (laughs) and that’s kind of a nice gift of spring!"

"Here comes a car. Sometimes I shine a light on myself so they know that we are here. Most people are nice. Every now and again they come tearing by, you know, in a hurry, or think they are."

It’s an unusual sight to see… people walking back and forth down the road in a type of vigil with flashlights. I asked Bill if people ever wonder what the heck he’s up to.

"Sometimes it’s really sweet. We’ve had a couple of occasions when in the last few years we’ve been doing this where someone will stop and they might even live just down the street from a place where there is spotted salamanders and wood frogs and spring peepers and Jefferson salamanders and others (cars driving by) but especially the spotted salamanders. If they’ve never seen em before, they just can’t believe that they live so close to such a beautiful creature and its really special to see them stop like that. And sometimes people want to help and get out but you worry about them because they might be in high heels or wearing all black."

"Whenever I see a car after we just crossed somebody, like brett up there is about to cross a woodfrog, it always makes me feel good. Cuz I think, okay that’s one that might have gotten squished….. I think what it’s taught me is if I really don’t have to go someplace on a rainy night in the spring when the ground is clear. You know one little ingredient that I could probably do without for a dish, I try not to drive. That’s one thing that’s really changed for me besides loving the animals is just you know one car on a little errand that seems so important at the time can really squish a lot of friends."

Road mortality

Even with a bunch of volunteers out here combing the street tonight, it’s still impossible to keep all the frogs and salamanders safe.

"Aww almost made it! Didn’t make it. That sucks." Brett bends down and picks up a frog that’s been flattened on the road. It’s a foot away from the edge of the pavement, and was almost in the clear to enter the vernal pool.

Only the frog’s leg is recognizable and in tact. The rest of the body is mangled, with it’s organs falling out onto the pavement. She tosses the frog’s body to the side of the road so scavengers such as raccoons won’t get hit by cars too. She then marks the frog fatality on her clipboard. Right now it’s just one frog, but it’s representative of what’s going on at a bigger scale.

"You know, how many cars have come though here, barely any! And still they’re getting hit. (gets out clipboard) there was a study in NJ, (sighs) that found that an average rate of 15 cars per hour was enough to kill more than half of the amphibians that were on the road. And 15 cars per hour is not that many."

Saving a couple dozen frogs and salamanders in a single night might seem like a drop in the bucket, but it’s important to recognize the long term impact. A spotted salamander can live up to 30 years – and that means that there are decades when the animal can breed and boost a population. When a salamander is killed by a car – we’re not just losing out on one salamander but the multiple generations that would have been created.

“There are hundreds if not thousands that are dying on the roads every rainy night. The ones that are dying are breeding adults. Spotted salamanders are a fairly long lived species and there’s a chance that their vernal pool will dry up before their eggs hatch and their young are mature and ready for life on land. So it’s not uncommon for them to have catastrophic breeding failure…. And they wont have any young that survive that year. So for them the trade off or adaptation that they made is that they come back year after year to breed. So if you remove those breeding adults from the population, over time, you might not have spotted salamanders anymore. And you can also make the argument that every individ. Is worthy… but there's a scientific argument for protecting the populations of breeding adults of long-lived species."

It's Not Easy Being Green

Cars aren’t the only things hurting amphibians these days. In fact, researchers believe that in the last 30 years, an estimated 200 amphibian species have gone extinct.

"Research shows that globally amphibians are in decline. They’re struggling particularly from habitat loss and disease and certainly climate change will continue to play a role in the spread of disease, the impact of the diseases and also for our local amphibians and their breeding in vernal pools and temporary wetlands, how long will those pools hold water each year…that’s a big question so there’s certainly other research that shows that there are a lot of challenges facing amphibians and road mortality is a huge challenge. There have been studies that have shown jawdropping numbers of amphibians dying on roads each year. And so ontop of all of those other stressors, they need all of the help that they can get."

Since starting the program, the salamander crossing brigades have helped more than 35,000 amphibians to cross the road.ButBrett acknowledges that the crossing bridgades’s work is labor intensive, and not the best solution for the problem… but it’s part of a bigger plan.

"This isn’t the most effective solution to the problem. A better solution for the long term would be to have detours around these sites or to temporarily close these roads or in some places they are putting in tunnels to allow the amphibians to pass under the road and not have to deal with traffic. And I think thaose all make a lot of sense, but you can’t have any of those things until you know where the crossings are and have some data to justify closing a road for instance. You wouldn’t close a road for five salamanders but you migt wat to close a road for 500 salamanders on a given night. Our goals are in the long term is to try to inform some of the community level decision making and get people inspired to start thingking about closing the roads for critters every once and a while."

A Familiar Face (and Spots)

And it’s not just random amphibians crossing here. Spotted Salamanders have site affinity, and cross the same roads year after year to use the exact same vernal pools. And we know this because the volunteers keep track. Spotted salamanders have bright yellow polka dots on their backs that are like finger prints – no two are the same.

"The spots on their back are actually a unique pattern, kinda like finger prints in humans that is unique to the individual. So we can actually tell one individual from another based on their spots. So anyway weve been taking pictures of the spotted salamanders that cross the road at this site for the last four years and every year we encounter at least one or more individuals who we’ve moved across the road before which is really exciting to think of them as individuals and not just a generic salamander.”

Conclusion

As the night goes on, the rain starts to let up and it’s starts to feel a little colder. I notice that there seems to be fewer and fewer frogs who are trying to cross. Brett agrees.

"It is winding down yeah. The rains slowing, the temperature is cooling. This is what happens when things start to slow down. Plus the people start to get wound down too once it reaches a certain time people get tuckered out."

Brett shares her tally for the night.

"So my tally is 21 woodfrogs, and 30 peepers, and one spotted salamander. And one redback salamander…Which is still, for this site, a small night. But its not nothing."

As I walk down the road, it starts to sink in how many frogs are killed here on a given night in the springtime. Humans (myself included) will never give up cars, and it seems like an endless battle that amphibians can never win.

Brett agrees, but shares her own optimistic perspective.

"The bigger picture of this is that it’s hopeful, people are taking time out of their nights to be uncomfortable in service to another species," says Brett. I think it’s meaningful for everybody who comes out here to …..be part of this amazing phenomenon of the spring migration…..The idea of thousands of amphibians moving across the landscape, all at the same time, while the rest of you are indoors sleeping or just tucked away, it’s something special and magical that we all get to be a part of."

Special thanks to Brett Thelan, Bill Strupe, and all of the fellow Salamander Brigadiere’s out there in NH. Since talking with Brett, the Keene City Council voted unanimously to close a street on rainy nights to ensure that amphibians could cross safely – the first road closure like this in the state of New Hampshire. And that road closure was due in large part to all of the data gathered by Brett and her volunteers.

To see a few photos from the night, a transcript of this story, and a link to the Salamander Brigadiere’s work, visit AnimaliaPodcast.com. That’s A-N-I-M-A-L-I-A Podcast dot com.

Thanks for listening!